As our population crosses the 2000 mark, one of the Association’s priorities is to explore evaluation protocols that owners can use when choosing breeding stock. Our goal is to preserve the limited genetic diversity while ensuring we maintain a healthy population exhibiting the best traits from the island. We invite you, our membership, to lend your thoughts for developing these protocols. Some traits to consider are parasite resistance, hardiness and skeletal structure. Are there other items you would like to be considered?

Below is a reprint of an article to spark the thought process. Written by The Livestock Conservancy’s technical advisor, Dr Phil Sponenberg, it discusses the potential effects of removing genetics from the population, in reference specifically to coloration and supernumerary teats. It’s a cautionary tale of how arbitrary decisions can affect the genetic diversity of the population, create issues and ultimately extinction of the breed. It’s a reminder that the dismissal of portions of our population can have disastrous effects.

San Clemente Goats, Culling, and Breed Standards

Originally Printed in the Sept/Oct 2008 ALBC News (American Livestock Conservancy) By D.P. Sponenberg

Editor’s Note: One of the challenges we face as breeders is that of balancing diversity with breed improvement when making culling decisions. Conservation breeding strategies require breeders to be much more tolerant of phenotypic differences for the goal of maintaining genotypic diversity. The following article gives a wonderful example of these issues of concern with a case example of a very rare breed. The conservation strategies utilized in this article could easily be applied to any breed.

San Clemente goats are an important genetic resource, partly because of their low genetic variability, but also due to their remote relationship to other goat breeds in the USA. This genetic treasure must be guarded carefully, and breeders need to be clear-headed in their thinking about what this “breed” is, and how to assure that it remains a resource for future generations.

San Clemente goats were only saved from extinction by the slimmest of threads. The vast majority of the animals of this breed comes to us through a handful of breeders who wisely kept and bred goats captured from the island. This number was never very great, which has important implications for managing this breed for the future.

With any breed, one question that needs to be answered is “what is this breed?” and a second is “which animals should be bred, and which not bred, to produce future generations?” There are two approaches to defining a breed, and both of these result in a breed standard. One is a prescriptive approach, which defines what the ideal animal of the breed should look like. This type of standard is typically used for standardized, production-oriented breeds. A second approach is descriptive, and describes the range of variation that is present in the breed. The differences between the prescriptive and descriptive approaches are important because they have profound effects on what the breeders actually keep and what specific genetic material is lost in ensuing generations. In short –standards shape the breed.

Two breed definitions of San Clemente goats are possible. One that can serve the breed well is “goats that descend in all lines from ancestor goats caught on San Clemente Island.” This definition encompasses all the variation, hidden and visible, that was present on the Island goats. A second definition is “goats that descend in all lines from ancestor goats caught on San Clemente Island, and that have an appearance typical of the majority of those goats.” The two are fundamentally different in how they shape the future of the breed.

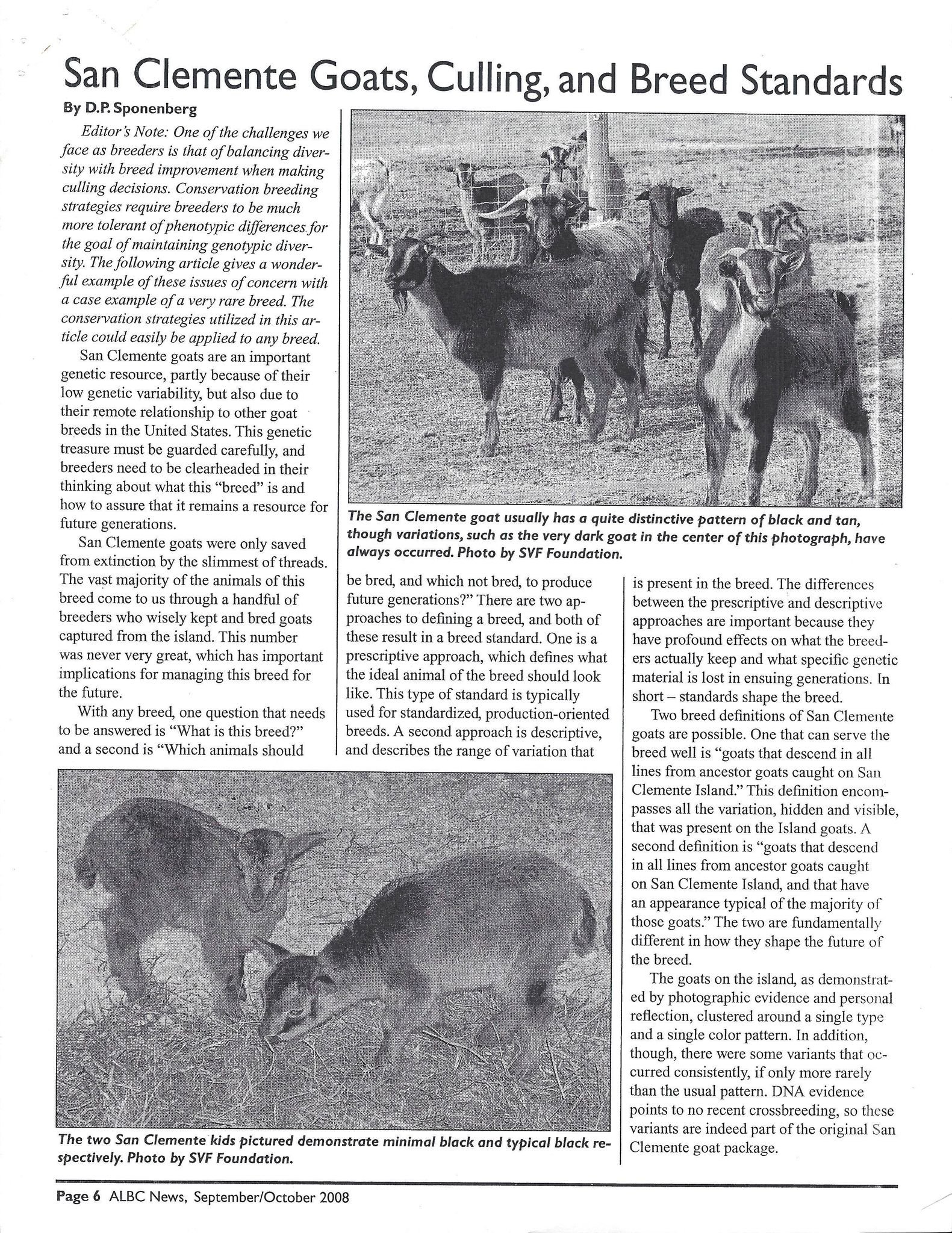

The goats on the island, as demonstrated by photographic evidence and personal reflection, clustered around a single type and a single color pattern. In addition, though, were some variants that occurred consistently, if only more rarely than the usual pattern. DNA evidence points to no recent crossbreeding, so these variants are indeed part of the original San Clemente goat package.

The San Clemente goat usually has a pattern of tan and black areas that is quite distinctive. As is typical of patterns in most breeds of goat, the pattern varies in the extent of black, and also in the shade of tan. The San Clemente goat is somewhat unusual, compared to other breeds, because the majority of them vary over an extremely small range –which means there is not much variation in most of them. In some few, however, the pattern is either less or more black than usual, and the tan is in some instances very pale compared to the usual pattern. In some goats the tan areas are nearly white. No DNA evidence has arisen to suggest that these goats are any other than real San Clemente goats, though, so it can be concluded that this pattern is consistent with a San Clemente origin.

Some breeders find the goats that are “palest tan” and “least black” to be unsettling, and refer to these as “white.” They are not white in the genetic sense, merely at the pale end of the usual pattern for these goats –and every bit as much San Clemente as their herdmates.

A second variation of color is the presence of white spots. White spots are very common in most breeds of animals, and completely removing all white spots from all animals of any breed is a long and difficult process.

The importance of the color to the goat breed is that each time a goat is removed from the breeding population on the basis of color, not only is the color removed, but also the entire genetic contribution of that goat is removed. This is trivial in very large breeds, but can drastically and irreversibly damage the gene pool of rare breeds such as the San Clemente goat. Color must be put into perspective –while uniformity may be a goal, it was not present in the original goats, was unlikely to have ever been present in the island goats, and insisting on uniformity in the descendants will hasten the demise of the breed to inbreeding depression. DNA evidence reveals that this breed is already minimally variable

A second controversial issue is the presence of supernumerary teats on many animals. This is a more substantive fault than is color variation. Supernumerary teats are frowned upon by dairy goat breeders for the good reason that these can interfere with milking. A few other nondairy breeds also penalize them (Tennessee Myotonic goats are an example) and other breeds tend to ignore them (Boer goats come to mind).

Multiple teats can and do cause problems in dairy situations, but in most other goat situations they are not usually a problem. It still makes sense to put some selection pressure against supernumerary teats, but if too many goats are culled, then the breed will cease to exist.

The genetic status of the San Clemente goat is precarious. DNA studies reveal very little variation at the genetic level, much less than in most other breeds. This is reassuring in one sense, because it is telling us that the goats from the island were isolated for a long time. If other goats were introduced, they left little or no trace in the genetic character of the breed.

The low genetic variability of San Clementes is important as it affects breeding decisions for these goats. Breeds can, and do, go extinct simply because the last one dies. Extinction can be with a bang as the last one is eaten, or it can be with a whimper as a small population suffers from inbreeding depression and the last ones are simply less and less productive (and reproductive). Culling decisions in rare breeds, and the San Clemente is disastrously rare, must be undertakencarefully for a variety of reasons. Considerations of primary importance must be breed survival, then production traits, and then fancy traits. Every goat is important to the future of this breed.

One good way to proceed is to realize that EVERY female goat will ideally leave a few offspring. Males are somewhat less critical, but it is easy to overuse a male so that he becomes a genetic bottleneck. This breed has clearly had significant bottlenecks in the past, and needs to avoid them in the future.

Culling for color variation (too white, white spots, other variants) should not be done in this breed, especially on the female side. The variation that is there is inherent in the breed, and by eliminating those does from reproduction the breeder is also eliminating the entire essential genetic contribution that those does could be making to the breed. If bucks of odd colors are from rare bloodlines, then they need to be used. When bucks of odd colors come from more common bloodlines, then (and only then) does culling for color make sense. And, it only makes sense if the breeders decide to change this breed into a single-color breed, which it was not on the island, and is not today. The breed can be changed, but breeders must not fool themselves into thinking that they are recapturing lost purity by choosing a single color. The breed is predominantly one color, but the other variations are just as pure as the predominant one.

Culling for multiple teats is more perplexing. At this point it likely makes little sense to cull does for multiple teats. In most cases it is possible to try to put more pressure on the male side of the equation. If a buck with multiple teats has a brother with only two, then it makes sense to use the one with only two teats. In some cases, though, culling bucks with multiple teats will cull entire, families, and that weakens the breed considerably.

If the San Clemente goat is to exist twenty years from now, then numbers are going to need to expand, and the entire spectrum of the current breed is going to need to contribute to that. Drastic culling assures that the breed will be uniform –but only temporarily as it drifts slowly and inevitably to extinction. This unique and beautiful goat deserves better than that!